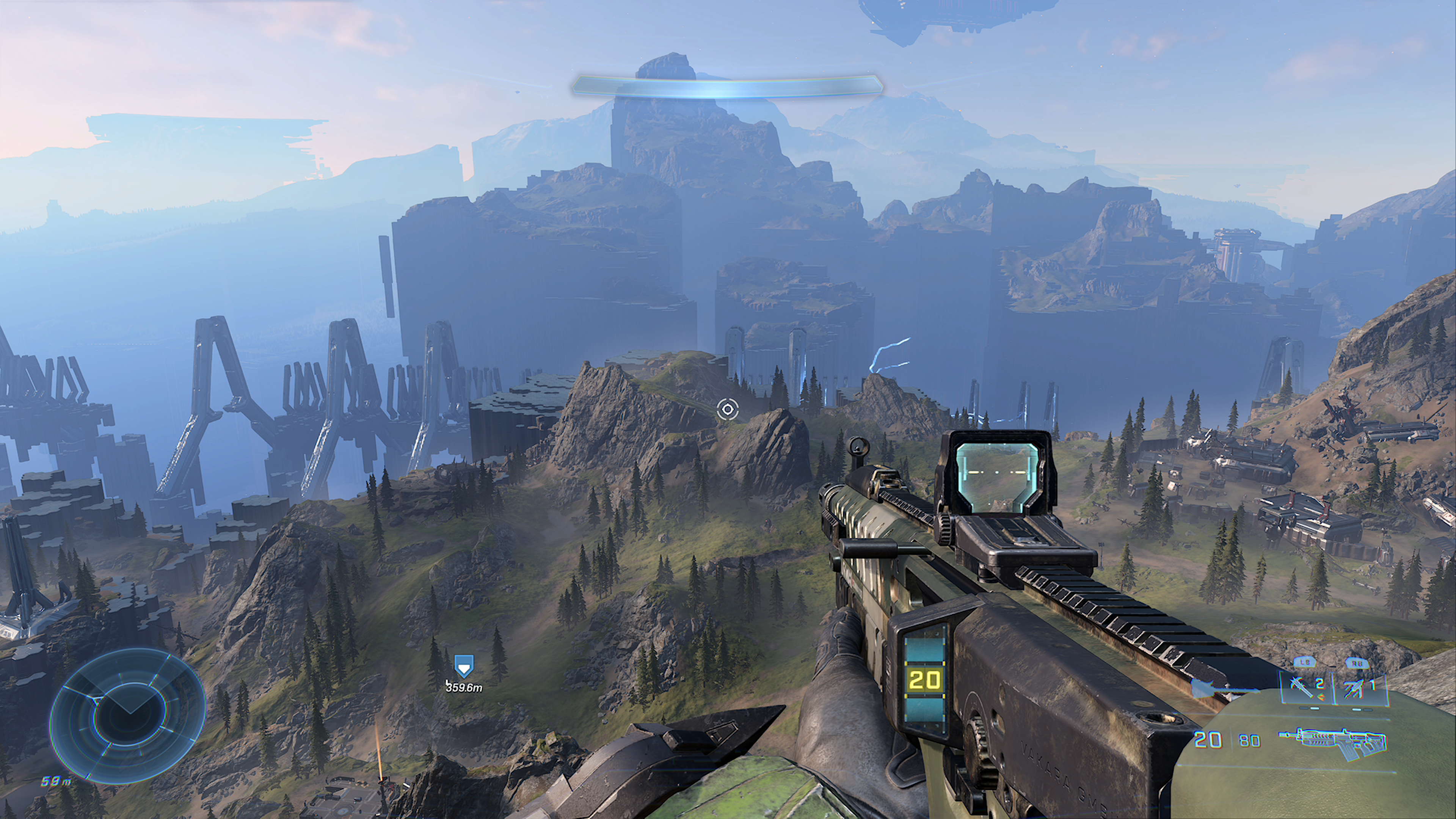

There’s a second side to Infinite, however – and that’s where the contradiction creeps in. While deeply traditional and dedicated to restoring Halo’s core, it’s also a highly experimental entry in the series. Its new ideas about open-ended play are very different to anything the series had attempted before – and yet, these new ideas had to mesh with Halo’s classic ‘golden triangle’ of guns, grenades, and melee to create something new that is still undeniably in possession of the series’ greatest hits. “We had this same initial thought, y’know ‘Ahh – are we breaking Halo?’,” admits Halo Infinite Character Director Steve Dyck, when I mention my initial concern about hearing of Infinite’s open world ambitions. “But as you play more, you just find – no, it feels natural. It’s one of those things where when you see something that makes sense, you think, ‘why wasn’t this always here?’” In Infinite, nowhere is a better example of this than the Grappleshot, the game’s new grappling hook-style equipment that colors practically every action Master Chief can take in the game. In combat, the grappleshot is both an aggressive tool to get into the enemy’s face and a defensive one to escape when your shields are depleted. It can be used to pick up weapons from afar, or yank over environmental hazards. Of course, it can also be used for traversal – and for much of the game is your primary tool for wandering the open map of Zeta Halo. Surprisingly, however, despite feeling so integral to the Halo Infinite experience, it wasn’t always so. “One thing that’s worth noting is that we have a sandbox team that’s developing in parallel for campaign and multiplayer,” explains Paul Crocker, Infinite’s Associate Creative Director. ”The goal is to take the best things that work for the game you’re making and make sure we’re using them. When we saw the Grappleshot, it was like, yep – cool. Let’s try that out. “I would probably say that the first thing that happens when you show the Grappleshot to the team and you’re two years from shipping, or three years from shipping, or whatever it was, and everything is broken in the game… You go – ‘here’s a tool that’s going to break more!’ Everyone goes – ‘No!’,” Crocker laughs. The key to getting over that hump, Crocker argues, is in play. Or as the saying goes, the proof is in the pudding. No matter how much initial reticence or fear there might’ve been over a mechanic like the Grappleshot to begin with, as soon as people got to using it, how fun it was to use began to trump any of those concerns. “It’s just about recalibrating people’s expectations,” Crocker says, speaking of both the development team and, ultimately, of players. “When you’re relying on being able to put walls around things to stop people from getting out of the maps and stuff, you design a game in a certain way. As soon as you teach players, teach the team – everyone gets on the same page. They say, ‘I get it, it’s about freedom’, or ‘I get it, it’s about this. We have to come up with creative solutions about X or Y.’ Then it becomes actually very easy, because you’re always thinking ‘I know the player is gonna get there’, not ‘what if they get there?’” Dyck concurs, noting that over the course of the development process, the Grappleshot’s utility was ultimately increased, rather than lessened. The more the team at 343 Industries tested the mechanic, the more they realized that this wasn’t just another piece of equipment – rather, it was a vital piece of the puzzle of the game they were creating. A tool so potent that, as I noted in my review, it practically feels as integral a component as Halo’s ‘golden triangle’, as established by Bungie 20 years ago. “When we initially put it in, it wasn’t there right at the very start – you didn’t start out with it,” Dyck says. “The things like the upgrades and the cooldowns – they were much more aggressive. The cooldowns kinda felt a bit… ‘aw man, I’ve got to wait for this thing to cool down before I can use it again?’ “The overriding factor of all of this was that whenever you were using it you were having so much fun that it just became this mindset shift of… okay, we know this is going to be hard to support everywhere – but it’s so worth it. Let’s just give the player the Grappleshot from the start, because we know they’re going to use it, all the time, all over the place, and just embrace that this is a change that we’re going after.” In this and several other ways, the Grappleshot feels demonstrative of a core idea that drove the development of Halo Infinite – of a painstaking search for the perfect balance between several disparate elements. Probably one of the most important elements to keep even scales on is a key part of Halo’s sandbox - and that’s the stuff that is actually, you know, a little bit broken. I recount one of my favourite ‘emergent’ campaign moments to Dyck and Crocker, where I called in a vehicle only for a lone Marine to wander right onto its landing pad. He greeted the Master Chief – only to be crushed by the dropped ordinance. His ally screamed out in anguish. It’s a dumb moment, but also funny – and exactly the sort of thing I associate with tooling around a Halo sandbox. “A lot of other games, it’d be like ‘nope, that’s a bug, must fix’,” admits Dyck. “One of the fun things about the Halo franchise is that it’s always had that sense of levity,” posits Dyck. “Grunts say goofy things, Marines say goofy things. So when a goofy thing happens, it’s okay for it to happen in the universe that we’ve created, right?” “We always prioritized fun, and how it makes you feel. I think actually the irony of a bunch of this is, the emergent stuff – some of it comes together quite late. Because until everything is connected you don’t know what’s going to emerge,” adds Crocker. “The fact that the game holds up and allows that to be true – crossed fingers – is one of those moments for us… and then we’re starting to predict, ‘well, what would happen if you did all of these things’, and… that’s the beauty of Halo, right? We build a sandbox so that people experiment and have fun. Nothing is too much fun – it’s really just us breaking out how to not break the game completely.” Developers are well aware, of course, of the concept that a bug is ‘shippable’. But for the Halo team this almost takes on a different meaning, where interesting behaviors emerge that were unexpected. Ultimately, the developers wouldn’t want to fix these even if they had unlimited time and resources – because it’s all part of the fun. I feel like a lot of the best sandbox-based games have the ability to facilitate this sort of thing. I don’t think it’s any surprise to see explosives and the sandbox used for game-breaking traversal in much the same way as Zelda: Breath of the Wild’s stasis launched a vast number of speed-running strategies. Halo Infinite has that energy. And it seems like that was intentional. “We really worked hard to not make the thing feel like a curated design experience,” says Crocker. “In the past, it got to a point where… ‘Here’s a combat bowl, here’s the weapon you want, go get it.’ Which is cool, if you want that very linear Halo experience. “But all the things we’ve talked about were also about trying to ensure… y’know, we used ‘Super Soldier Base Assault’ as an example all the way through the game. Now, to us that means ‘there’s a problem, deal with it however you want’. You have 360 degrees of freedom – go and do it.” This wasn’t always easy for the developers, of course. Some of them have been working on the Halo franchise for two decades – and so bringing a new approach to the series is complicated. But as with the grappling hook, Dyck and Crocker describe it as an iterative, growing process: the more of the experience was playable, the more people began to understand what the change meant for Halo, and why it was going to work. And all the while, throughout development, there was another clear secondary goal: to ensure those who didn’t want to necessarily engage with some of the game’s newer ideas wouldn’t absolutely have to. “Our goal was always that if you want to play a linear Halo game in the traditional sense, where the story pulls you through – cool, it’s there,” Crocker notes. “You always know where to go next. The simple answer is that you put things on the way to entice you off that main path, and we do that too. “But we have fans, we have players, we have people who just aren’t interested in anything off that main path. The first thing they want is that Master Chief story adventure. But then they come back at the end and they’ll realize that they have half the game that they can start messing around with and get more powerful. “We also have people like one of our art directors who only plays in a ‘collect 100% as he moves through the map’ way. He’s done this like four or five times in front of me. So when he rolls up at the first Spire, he’s pretty powerful as a player from a vehicle- and weapon- and everything-perspective, because he’s spent hours and hours just scraping every piece of content out of that world. It’s just a choice, right? “That’s, for us, the reason why we made the game the way we did. Halo should be about evoking this feeling of Master Chief as this unrelenting force of hope and power – but nobody tells you what to do, so go do it the way you want.” This design is admirable, but also led to unexpected bumps in the road and complications. Dyck describes an evolved AI system where the game will react in subtle ways to things like how you arrive at a combat encounter. You could enter a battle from any direction, on foot or in a vehicle, alone or with marines in tow. You could even be sniping from afar. Infinite’s AI had to be adjusted to react to this – something quite different from the encounter design of some of the past Halo titles. It turns out that this sort of area is where Infinite benefited most from its lengthy delay – pushed back from the Xbox Series X/S launch a full year to holiday 2021. It was a surprising and ballsy move on the part of Microsoft - both in terms of a show of faith for its development staff, but also a willingness to essentially gut its launch line-up. With hindsight we can now say that this has paid off. Bbut that was never guaranteed. “The level of balance that we’ve gotten to and the pacing and stuff like that was really helped by the extra year of development that we had,” Dyck emphasizes. “The easy trap to fall into would’ve been to say: we’re adding. Adding, adding, adding. But right out of the gate we were like – nope, if anything, we’re removing stuff to get a better sense of pacing and flow and an all-out better-feeling game. That was huge.” “First of all, getting the opportunity to do this and reassess where we were at and what we had. Pick a dozen areas of focus that are already pretty solid – now we’re gonna make them great, and then dial back some of the other stuff. We didn’t want to fall into the trap of… ‘y’know what we need? A new boss, or a new enemy variant, or a new gun’. It’s like, no, we’ve already got really good stuff – we just need to craft and polish what we’ve already got in the game.” “A year ago, you could play the game. It’s true, it wasn’t finished, but most of the stuff you see today was in it – it just wasn’t as polished. [The delay] really just gave us those opportunities,” admits Crocker. But that polish has carried the game far, and it stems from a brave decision to delay. “We were supported to make that decision. Which, it’s incredible, to have that level of support. It’s not as simple as the thing we’re working on [at 343] - there’s a whole organization around it [in Microsoft], as we all know.” And now, it’s time for the team to rest. At least for a while. They’re of course thinking about the future, and have left the campaign with plenty of ideas they’d like to take forward in future. But there’s nothing to announce right now. “You’re not going to get your exclusive,” Crocker laughs when asked about future plans. For now, as this chat took place, right after the game’s launch, the team appear to be enjoying watching fans experience their campaign online – and, just as was touched on earlier, a lot of it is about watching people use those sandbox tools to crack the game wide open like an egg. And they love it. “That’s part of the fun of Halo! We know that fans are going to intentionally do that,” Dyck grins. “Like, oh, I see these blockers you put up to stop me getting my Ghost in there - I’ll show you! I’ll get my Ghost in there. And inevitably they do! When they do, it’s awesome – ‘cos we’re like, okay, you spent a half hour trying to get your Ghost in there, and at the end of the day, you did? Awesome! Go fight a boss with your Ghost, or with Marines, or something like that. “It’s all part of what makes Halo unique.”